What Can Scammers Do with Your Phone Number?

When cell phones first became popular, no one thought they’d become what they are today. For the first few years, it was …

Social engineering is a technique that takes advantage of human psychology to obtain access to a company’s systems or data. Unlike traditional hacking methods that rely on the exploitation of system vulnerabilities, social engineering attacks encourage individuals to break established security protocols.

As a practice, social engineering is as old as human history itself.

The Ancient Greeks used the Trojan Horse to gain entry to Troy, and many centuries later, it was employed by the infamous Charles Ponzi to deceive investors as part of his well-documented scheme.

Later, in the 1990s, cybercriminal Kevin Mitnick set out to manipulate the hardware in a Motorola cell phone. He telephoned the company with a small request to speak to the project manager, but was transferred eight times and ended up speaking to the VP of Motorola Mobility.

Over the course of those transfers, Mitnick learned the company had a research centre in Illinois. He then pretended to be an employee of the centre, built trust with the VP and later obtained the project manager’s number.

Mitnick later discovered that the project manager Pam was on vacation, so he told her colleague that Pam had promised him the source code for the cell phone before she went on leave.

The colleague, Aleesha, was ultimately convinced to provide Mitnick with the username and password for the company’s servers. While Mitnick did not use or sell the code, the narrative he constructed to deceive and manipulate shows the power of social engineering.

In the digital age, social engineering convinces the victim to contravene cybersecurity protocols, releases sensitive personal or financial information and permit access to the company’s networks and systems.

While the underlying premise of social engineering has not changed in millennia, the methods of attack have become more diverse, sophisticated and effective as technology has evolved.

Automation enables criminals to send millions of phishing emails and SMS messages simultaneously, while VoIP technology enables them to make cheap and anonymous phone calls from anywhere in the world.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are also exacerbating the problem. AI-powered deep fake technology, for example, was recently used in a social engineering attack.

Deep fake representations of key staff in a British firm were present on a video call where scammers asked another employee to carry out a secret transaction on behalf of the CFO. Such was the realism of the deep fakes that the employee in question authorised 15 separate transactions worth around £20 million.

Social engineering has also become easier since people share more of their lives in public. As we will learn later, this tendency makes it easier for bad actors to craft plausible and engaging stories that deceive victims.

Social engineering can be used for various malicious purposes, but most rely on the successful manipulation of the victim’s fears and emotions. Attacks also create a sense of urgency to avoid the victim having time to properly contemplate their request.

To that end, social engineering attacks tend to exhibit one or more of the following characteristics.

Malicious actors pose as trusted individuals to obtain the victim’s confidence. This can involve the impersonation of coworkers, authority figures or another company such as a financial institution.

To further enhance the sense of trust, some actors will collect publicly available information about the victim or the company and incorporate it into a plausible story or reason for contact.

Social engineering exploits various emotions in the victim. Let’s take a look at a few of the most common.

Fear is an easily manipulated emotion that tends to elicit a panic response where the victim wants to avoid the situation as quickly as possible.

In the workplace, fear often relates to having:

Aside from fear, social engineering attacks almost always include some form of urgency. The objective – as we touched on briefly above – is to have the victim act before they think.

Curiosity is used as a form of bait where the victim is lured into seeking clarification or taking some type of action.

In this case, they are often asked to confirm details inside an attachment infected with malware. Others may be sent an email with a provocative or attention-grabbing subject with contents the victim can’t help but click on.

One of the more nefarious social engineering tactics is to play on someone’s desire to be helpful.

Bad actors often search out new employees who want to make a good impression and are less informed about cybersecurity threats.

Having said that, the hierarchical structure found in most organisations means employees are helpful by default if asked by a (real or otherwise) superior.

Victims may receive a text message asking for help from someone purporting to be their boss. Emails may also be sent that ask victims to contribute to a charity or cause their boss supports.

Social engineering attacks that exploit greed tend to be associated with a financial reward of some kind.

In some cases, the reward may also be power or status-related.

Excitement-based attacks use attractive incentives to invoke enthusiasm, anticipation or eagerness in the victim.

Irritation is tied to urgency in that people are more likely to become impatient with frustrating or distracting tasks. Based on this, they may rush task completion without due care or proper verification.

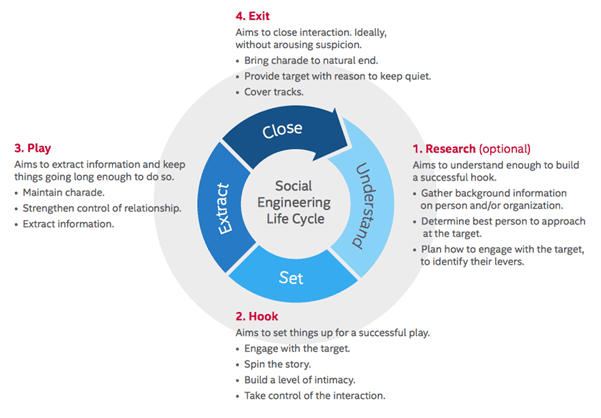

A social engineering attack typically unfolds in four distinct phases.

Each phase involves particular techniques designed to coerce the target into revealing information or acting in ways that compromise security.

The first step for any bad actor is to identify someone who has what they want. This is usually an employee with access to login credentials, confidential information, money or data.

Attackers also collect information from various such as social media profiles, company websites, public records and press releases.

Later, they use this information to craft a personalised story that is more likely to see the victim let their guard down.

The objective of the second phase is to initiate contact with the potential victim. To do this, attackers look for an entry point which may be an email address, social media account or phone number.

The attacker then reaches out with a hook to prompt the victim to engage. For example, someone may contact a recently promoted employee with a job offer from another company.

When the victim takes the bait, so to speak, the attacker employs their social engineering tactic of choice.

Returning to the previous example, the employee may be directed to set up an online interview. Once the link to the interview is clicked on, however, malware is installed on the employee’s device.

We’ll go into more detail about specific tactics in the next section.

In the retreat phase, the perpetrator vanishes after the attack has been carried out. They aim to avoid detection by leaving as little evidence of their indiscretion as possible.

Of the various social engineering tactics, phishing is by far the most common.

According to the FBI Internet Crime Report 2023, phishing topped the list of crime types with 298,878 complaints across the year. This number was more than five times the second most prevalent crime.

Phishing attacks occur when scammers use any type of communication to “fish” for information. Email is the most prevalent medium, and the messages contained therein look identical to those sent by legitimate sources.

In many instances, phishing plays on the victim’s fear. They may receive an email informing them that their account has been compromised, while another employee may be contacted by a major supplier with an overdue invoice that must be paid immediately.

Other types of phishing include:

According to the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC), business email compromise is in the top three cybercrime types for businesses.

Both effective and lucrative, BEC cost 2,000 businesses almost $80 million in 2022 and 2023. It is a type of email fraud where criminals deceive employees into revealing important information.

There are three core ways social engineering is used to facilitate business email compromise:

Baiting is a type of attack where the victim is lured into some harmful action based on the promise of receiving something desirable in return.

Consider a CRM employee who receives an email from the company’s software vendor. The email offers free access to additional features, but the relevant link points to a website that installs malware on the company’s system.

Tailgating occurs when an unauthorised person follows closely behind an authorised person into a restricted area. The most obvious example is an employee who uses a keycard to access a secure area and inadvertently facilitates unauthorised access.

Piggybacking is slightly different in that the unauthorised person convinces the other person to let them into the restricted area. To do this, they may have their hands full with equipment or paperwork and ask the victim to hold the door for them.

Other scammers will pose as delivery drivers or simply state that they left their keycard at home.

Pretexting involves the abuse of a legitimate role or the creation of fake personas in companies. The success of pretexting relies on the attacker’s ability to create a believable story and present themselves as a trusted entity.

As part of his role as systems administrator at the NSA, Edward Snowden convinced about 24 of his co-workers to provide their usernames and passwords. Snowden used those credentials to access documents that he would later leak to the press.

While social engineering attacks are increasing in diversity and sophistication, most follow a similar pattern and rely on emotion to be successful.

Here are some simple things an organisation can do to protect itself.

Malicious actors want employees to think before they act. Individuals should be skeptical of communication that instils fear or urgency – especially atypical communication.

Employees are encouraged to review all requests and if one seems too good to be true, then it probably is.

Data breaches facilitated by social engineering take around 270 days to identify and contain, so the attacker is often long gone before anyone notices.

Any stolen data or information may also be used in subsequent attacks.

Verify the details of suspicious emails for authenticity. Check for spelling and grammar mistakes as well as the domain listed in the email address.

If an email appears to have come from a legitimate company, it is also important to verify that its email and website match and are authentic.

While some discrepancies may be easy to spot, others will be overlooked over the course of a typical workday where other tasks compete for the employee’s attention.

Cybersecurity firm Abnormal Security found that only 2.1% of all business email compromise attacks were reported by employees. For a medium-sized business with 1,500-2,000 employees, this equates to 30 or 40 attacks every day.

Some employees delete suspicious emails and because they haven’t interacted with the scammer, feel there is no need to report it. Others fail to report incidents because they’re embarrassed or want to avoid creating more work for the security team.

Whatever the reason, it is crucial the organisation creates a culture where employees feel comfortable making reports. Above all, they must understand the importance of doing so.

In addition to patterns in the method of attack, there are also patterns in the email subject lines attackers use.

Employees must be wary of subject lines that are blatant attempts to rouse their emotions. Some of the most common lines incorporate words such as “Urgent”, “Important”, “Important update” and “Attn”.

Subject lines may include derivations of:

If employees receive an email with links or attachments from someone they know, they should still verify whether that person sent the email. This is particularly true if the communication feels out of character.

With account takeover and thread hijacking an ever-present possibility, it is good practice to err on the side of suspicion.

In summary:

References

When cell phones first became popular, no one thought they’d become what they are today. For the first few years, it was …

When Mr. Beauchamp watched a video of Elon Musk – the world’s richest man – recommend a certain investment platform to make …

Your company delivered the good or service it promised to a client and now it’s time to collect the funds owed to …

Eftsure provides continuous control monitoring to protect your eft payments. Our multi-factor verification approach protects your organisation from financial loss due to cybercrime, fraud and error.