What Can Scammers Do with Your Phone Number?

When cell phones first became popular, no one thought they’d become what they are today. For the first few years, it was …

The broad term “hacker” describes any individual who is skilled at computer system manipulation. Note that a hacker does not necessarily have malicious intentions, and not all hacking is illegal.

Conversely, a hacktivist is a type of hacker motivated by political, social or religious issues. Hacktivists may be individuals or groups of individuals who share similar ideologies.

While the two terms are used interchangeably, it is clear that each refers to an entity with different methods, motivations and objectives.

Hackers are individuals who access computer systems, devices and networks and exploit them for personal gain.

Most are motivated by financial rewards, but others may do so:

Hacking as a practice predates the internet itself, with the first recorded instance at Bell Telephone in 1878. Several phone operators employed by the company to run the switchboards were known to prank callers by disconnecting or misdirecting their calls.

Hackers may be classed as either black hat, white hat or grey hat.

Black hat hackers are cybercriminals that illegally hack into systems with malicious intent. Once a vulnerability has been identified, they attempt to exploit it with a virus or malware.

Other hackers may encrypt or lock important files on a device or system. This can be seen in a ransomware attack, where black hat hackers block access and then demand a ransom payment for restoring it.

White hat hackers are similar to black hat hackers in that each individual searches for system vulnerabilities. However, these individuals work with businesses to identify and fix vulnerabilities before those with malicious intent can exploit them.

One example is a penetration test, where hackers perform a simulated cyber-attack on the company’s systems. This is an important way for the company to assess the security of its systems as well as its level of preparedness.

Grey hat hackers occupy a middle ground between black and white hat hackers.

They may not possess the criminal intent of the former, but they also lack the consent of the entity whose systems they’re hacking into.

Whether or not the intentions of a grey hat hacker are noble is up for interpretation. Some may identify security vulnerabilities without exploiting them, for example, but only make that information available to the organisation for a price.

Other hackers under this type may also help individuals or firms retrieve data or help them remove malware.

The term “hacktivism” is a portmanteau of the words hacking and activism.

To that end, hacktivists misuse technology to further social and political causes or express their discontent with those causes. They may act alone or in a group of people with similar views and objectives.

The prevalence of hacktivism increased in the 1990s in line with an increase in personal computer adoption. No longer confined to protests, boycotts or strikes, activists could harness the power of the digital age to spread their message.

Whether hacktivism could be considered ethical is both complex and contentious. Purists assert that hacktivism is a way to draw attention to important issues and expose corporate misconduct as well as increase transparency, accountability and freedom of information.

From a legal perspective, however, hacktivism is a crime – irrespective of whether its intentions are noble. Some hacktivist attacks cause substantial harm and disruption to a company and the effects may be no different to those inflicted by a hacker.

Critics of the practice also believe that hacktivism is simply a foil for malicious intent. Hacktivists have disclosed information that has later been exploited, and, like the hacker community, lack of individual accountability is also a problem.

Unlike hackers, hacktivists are less interested in financial reward.

Instead, their intention is to disrupt the continuity or stability of countries, organisations, events or society. In the process, hacktivists seek to advance a particular cause or create awareness around an issue they feel is overlooked.

In most cases, hacktivism centres around these common themes:

The objectives of some hacktivists are harder to understand. One individual may take a website offline to prove a point, while another may target an organisation that holds conflicting values.

In either case, the motivation behind the attack isn’t immediately obvious to the wider populace.

Since hacktivists are not motivated by money, their approach to vulnerability exploitation differs somewhat from that of a hacker. Ultimately, hacktivists want the target organisation (or society in general) to understand their displeasure.

So how is this achieved? Let’s take a look.

Online content is published by anonymous whistleblowers to reveal information about powerful entities. When particularly sensitive information is made public, the attack may be classed as doxxing.

Leaked information exposes the entity, raises public awareness and attracts the attention of the media. Yet more awareness is generated when the media credits the hacktivist and the cause they are advocating.

In 2015, a hacktivist leaked 400 GB of data collected by an Italian company that provided surveillance services to governments and law enforcement. Among other things, the data leak exposed the company’s various controversial clients.

Hacktivists will also hack into popular websites with the intention of defacing them with content promoting their own message.

This is known as a website defacement attack, where the intent is to embarrass or discredit an organisation and do damage to its brand and reputation.

In 2011, the website of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) was defaced by hacktivists who used the platform to condemn corruption and inequality.

In a practice similar to phishing, hacktivists take a legitimate website and then copy its content on a mirror site with a slightly different URL.

Website cloning is typically performed in response to censorship. It aims to ensure that content remains accessible and encourages freedom of information.

Geobombing is a popular technique for drawing attention to human rights issues.

Hacktivists add geotags to YouTube videos and link them to specific locations on platforms such as Google Maps.

The geotag tells the audience where the video was filmed and in some cases, serves as a form of documentary evidence. Other videos may publicise the location of a political captive or human rights advocate.

Distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks are another approach favoured by hacktivists. According to cybersecurity service provider StormWall, geopolitical motivations were the primary driver of hacktivist DDoS attacks in Q4 2023.

In a DDoS attack, the hacktivist floods a network server with traffic to prohibit legitimate users from accessing websites and online services.

Hacktivists were behind an attack on open-source platform GitHub in 2015. The attack, which originated in China, targeted two GitHub projects associated with the circumvention of that country’s censorship laws.

Though their objectives may differ, hackers and hacktivists use similar approaches in their attacks. This makes it easier for organisations to defend their software, infrastructure and sensitive customer details.

Here are a few tools and strategies a business can use to thwart these actors.

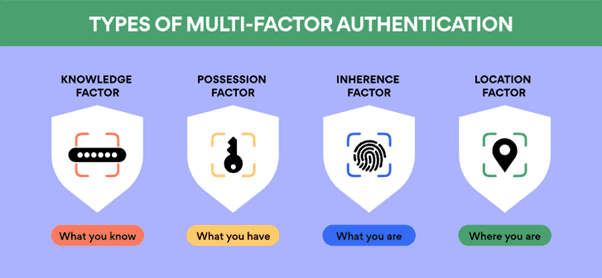

Multi-factor authentication (MFA) is an access control that adds another layer of protection to user accounts.

Should a bad actor phish or socially engineer a user’s password, MFA prevents them from accessing the account with a secondary authentication requirement.

In general, there are four types of MFA:

Where possible, organisations should also utilise the services of white hat hackers to test for system vulnerabilities.

Top companies such as IBM, Google, Dell, Tesla and Bank of America hire so-called “ethical hackers” who are required to hold Bachelor’s degrees as well as professional hacker certification.

The majority of organisations – especially larger firms or those in the public eye – benefit when they have a plan in place to deal with cyberattacks.

CSIRPs are complex documents that set out how the organisation will respond to a range of threat scenarios.

These plans also clarify individual roles and organisational policies, but perhaps most importantly, they minimise or contain the damage inflicted by the hacker or hacktivist.

In summary:

References

When cell phones first became popular, no one thought they’d become what they are today. For the first few years, it was …

When Mr. Beauchamp watched a video of Elon Musk – the world’s richest man – recommend a certain investment platform to make …

Your company delivered the good or service it promised to a client and now it’s time to collect the funds owed to …

Eftsure provides continuous control monitoring to protect your eft payments. Our multi-factor verification approach protects your organisation from financial loss due to cybercrime, fraud and error.