What is source-to-pay (S2P)?

Source-to-pay (S2P) is an end-to-end process in procurement that encompasses the activities associated with sourcing products from suppliers.

Australian tax law encompasses the legal rules and regulations that stipulate how taxes are assessed, collected, and distributed by public governmental authorities. Tax law tends to be specific to a particular country, but there are often similarities or common elements in the laws of different nations.

In Australia, federal taxes are imposed by the Commonwealth and then administered by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

To a lesser extent, taxes are also imposed by state and local governments under relevant laws.

The most important Acts that determine how the Commonwealth collects taxes include those related to GST and the payment of income tax by individuals and businesses.

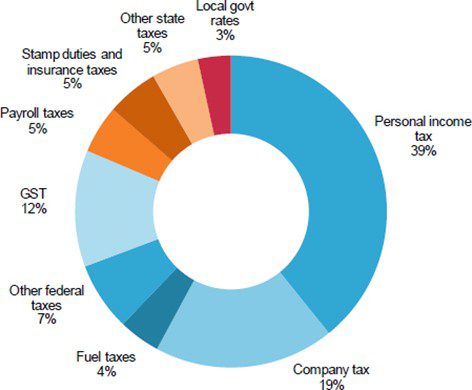

Why? Because these account for the majority of tax revenue collected by the Australian Government each year.

The collection of GST is governed by the GST Act, which is more formally known as A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999.

As a broad consumption-based tax, GST is similar to the VAT imposed in other countries. GST is levied at a flat rate of 10% for most goods and services that are sold in (or imported into) Australia.

Some items are exempt from GST, however. These include some exports as well as basic foods such as unflavoured milk, flour, sugar, tea, coffee, fruit, and vegetables.

Businesses and other enterprises that have a GST turnover of more than $75,000 (or $150,000 for non-profits) must also register for GST purposes.

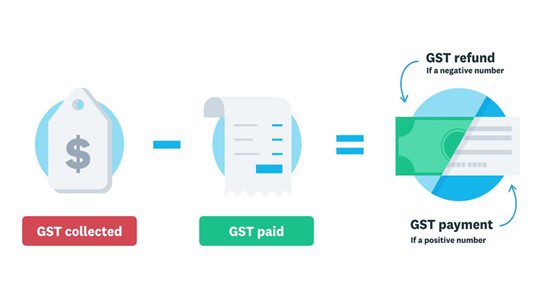

Depending on the amount of GST they collect via sales versus the tax credits they receive from GST paid on purchased items, these businesses may owe the ATO money or receive a refund.

The collection of income tax, on the other hand, is governed by two separate acts that operate concurrently. These include the Income Tax Assessment Act (1936) and the Income Tax Assessment Act (1997).

Income tax is collected on a progressive scale such that the more an individual earns, the more they are taxed.

The 1997 Act introduced capital gains tax rules after they were deemed assessable income. Other forms of income subject to taxation include government payments and pensions.

All companies in Australia are subject to a flat 30% tax on their income. However, small to medium-sized businesses with an aggregated turnover of less than AUD 50 million are taxed at 25%.

Irrespective of size, however, company tax is subject to residency and income source rules similar to those imposed on individuals.

In Australia, the federal government has authorisation to tax:

Rules that relate to an individual’s residency status for tax purposes are clearly outlined in the relevant legislation.

In short, non-residents are subject to the same tax rates and concessions as residents.

Legislation also clarifies whether income was sourced from Australia or from overseas. Generally speaking, Australian income is that which is derived from a place of employment or a fixed place of business.

On the other hand, income is derived from worldwide sources if the relevant contract was made outside of Australia.

Despite these delineations, tax laws for personal income are rather broad and sometimes open to interpretation. It’s important for residents to seek proper advice when it comes to taxes in Australia, to avoid potentially being liable for things such as tax return fraud.

This increases the risk that an individual’s income is taxed by more than one country.

To avoid such a scenario, Australia has entered into tax treaties with over 40 different jurisdictions.

Tax treaties – which are sometimes called double tax agreements (DTAs) or tax conventions – avoid situations where individuals are double-taxed on their income.

Aside from the obvious benefits to the taxpayer, tax treaties also benefit the Australian Government.

For one, they reduce instances of tax evasion and also encourage cooperation and respect between the ATO and the tax authorities in other countries.

As noted earlier, the federal government derives the power to impose and administer taxes from the Constitution.

However, some of this power is distributed to individual states as part of an agreement.

State (and indeed territory) taxes are imposed by the states and territories and administered by their respective revenue offices.

State governments are free to impose their own taxes based on state-specific Acts and regulations. However, these must not contravene the taxing power of the Commonwealth outlined in the Constitution.

While the federal government raises around 81% of all tax revenue, the states and territories collect most of the remainder via:

Just as the federal government confers taxing power to state governments, state governments also confer limited power to local governments.

Council rates – the main source of income for local government – is an example of taxation power conferred in this way.

Tax litigation in Australia differs substantially from other forms of civil and administrative litigation.

Most countries take a hybrid approach when it comes to tax litigation. To resolve disputes, they utilise a combination of special commissions (often comprised of senior public servants) and a judiciary power.

Australia’s broader judicial system is comprised of federal and state courts and tribunals. Some have inherent jurisdiction when it comes to tax disputes, while others make decisions within the confines of the relevant legislation.

In any case, it’s important to point out that there are no courts or tribunals dedicated to tax in Australia.

The ATO operates completely independently of the judicial system with its own procedures and checks, and this independence even extends to the level of funding it receives.

The vast majority of tax-related disputes are settled out of court.

With no dedicated tax courts or tribunals, this may come as no surprise. Compounding the problem is the fact that since most tax disputes never enter a courtroom, there is a lack of precedents or their development takes years.

Perhaps the most pertinent reason for the individual, however, is the added cost, time and stress associated with undertaking legal action.

So how are tax disputes between taxpayers and the ATO resolved in Australia?

Disputes that involve tax-related criminal prosecutions are handled by the police and the prosecutors’ office of the relevant state.

In serious cases, matters may be referred to the Australian Federal Police (AFP) and Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP).

The CDPP works under the Criminal Code Act 1995 and can prosecute various indictable offences such as:

For non-criminal matters and disputes that require mediation, the process is more nuanced.

The majority of tax disputes follow both legislated and administrative procedures to arrive at a mutually beneficial outcome, with many now settled by alternative dispute resolution (ADR).

ADR describes various mediation processes, but common to most is the presence of an impartial practitioner who helps resolve the dispute.

This avoids the need to involve a Judge or Magistrate.

ADR mediation processes include:

Alternative dispute resolution has several advantages over having the matter heard in court.

The ADR process tends to be quicker, cheaper, and more flexible. It also tends to be less stressful for the taxpayer and offers them more confidentiality.

Tax litigation is governed by the Taxation Administration Act 1953, and the tax litigation process starts when a taxpayer lodges an objection to a taxation decision.

The Act defines this decision as an “assessment, determination, notice or decision against which a taxation objection may be, or has been, made.”

In raising an objection, the taxpayer must explain “fully and in detail” the reasoning on which their objection is based.

While there is no formal burden of proof requirement for the taxpayer at this stage, the onus is on them to convince the Commissioner of their point of view.

If the Commissioner is unconvinced by the taxpayer’s objection and the taxpayer is dissatisfied with the decision, they can choose to appeal.

Many taxpayers will have the matter reviewed at the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) – one of the primary forums for tax litigation in Australia.

The AAT serves as an impartial practitioner since it has jurisdiction to review decisions made by the ATO, and tends to review cases based on the exercise of discretion (and not on those based on a question of tax law).

One section of the Act is significant for the taxpayer – s 14ZZK(b).

The section states that after the matter proceeds to litigation and the Commissioner has made an objection decision, the burden of proof is placed firmly on the taxpayer.

This process can be problematic for two reasons.

The first is that the taxpayer will be required to take a legislative stance to support their argument. In other words, they’ll need to possess or acquire knowledge of tax law.

The second reason is that taxpayers must prove under s 14ZZK(b)(i) that the taxation decision they received from the Commissioner was excessive.

If the decision was related to an assessment, for example, the taxpayer will also need to prove (with evidence) what the assessment should have been.

Note that at this point, the AAT may follow its own procedures to make a ruling and is not bound by formal rules of evidence. But it is permitted to admit new evidence that was not considered (or available) when the matter was raised.

If either party is unsatisfied with the outcome of the tribunal hearing, they may appeal to the Federal Court within 60 days of the AAT’s decision.

As noted earlier, these appeals deal exclusively with questions of law.

This means that for the Federal Court to have jurisdiction over the appeal, the appealing party needs to find an error of law in the AAT’s reasoning.

The ability to distinguish between questions of law and questions of fact can be difficult for the uninitiated, and this topic will be one of the first the court addresses in any tax appeal.

In March 2019, the AAT established the internal Small Business Taxation Division (SBTD) to deal with small business tax disputes. Provisions facilitating the SBTD are laid out in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Regulation 2015.

The SBTD enables small business owners to avoid some of the stress (and intimidation) of tax litigation against the ATO. It also addresses the often major discrepancies between the two parties in terms of expertise, time and resources.

Article references

Source-to-pay (S2P) is an end-to-end process in procurement that encompasses the activities associated with sourcing products from suppliers.

Reading a check may appear straightforward at first glance, but the various elements that comprise a check play a crucial role in …

A hedging strategy is a risk management strategy to avoid large financial statement losses due to investment fluctuations. Hedges work like an …

Eftsure provides continuous control monitoring to protect your eft payments. Our multi-factor verification approach protects your organisation from financial loss due to cybercrime, fraud and error.