Platform

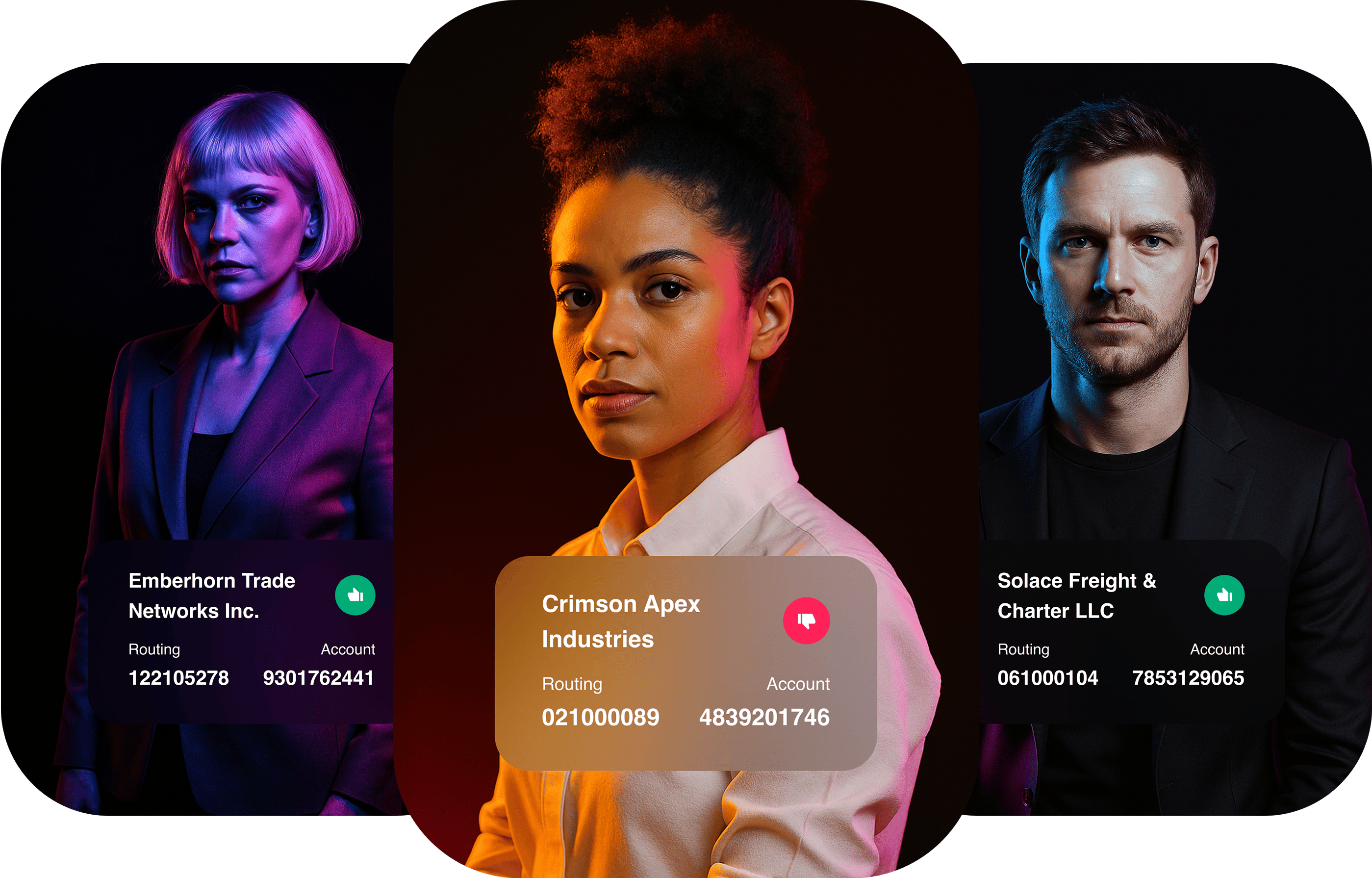

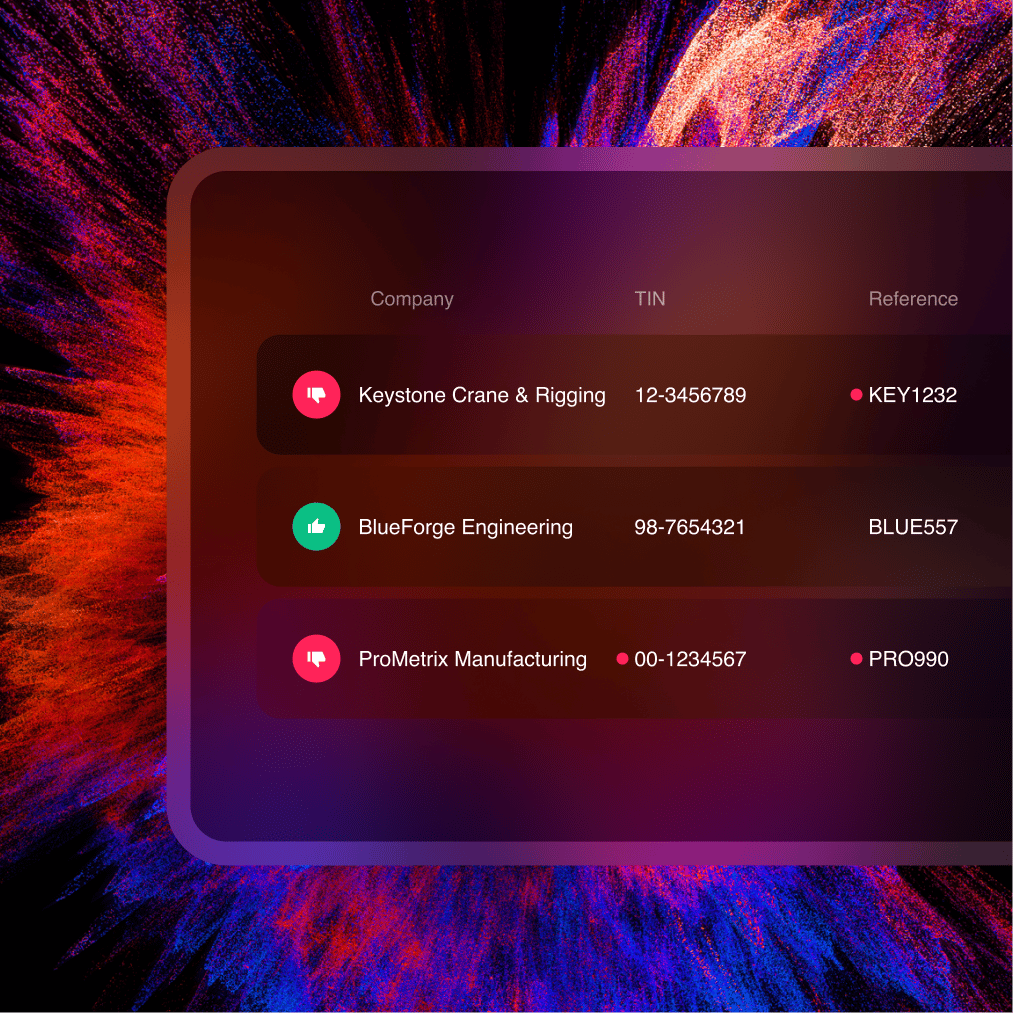

Supplier Management

Onboard, verify and manage suppliers

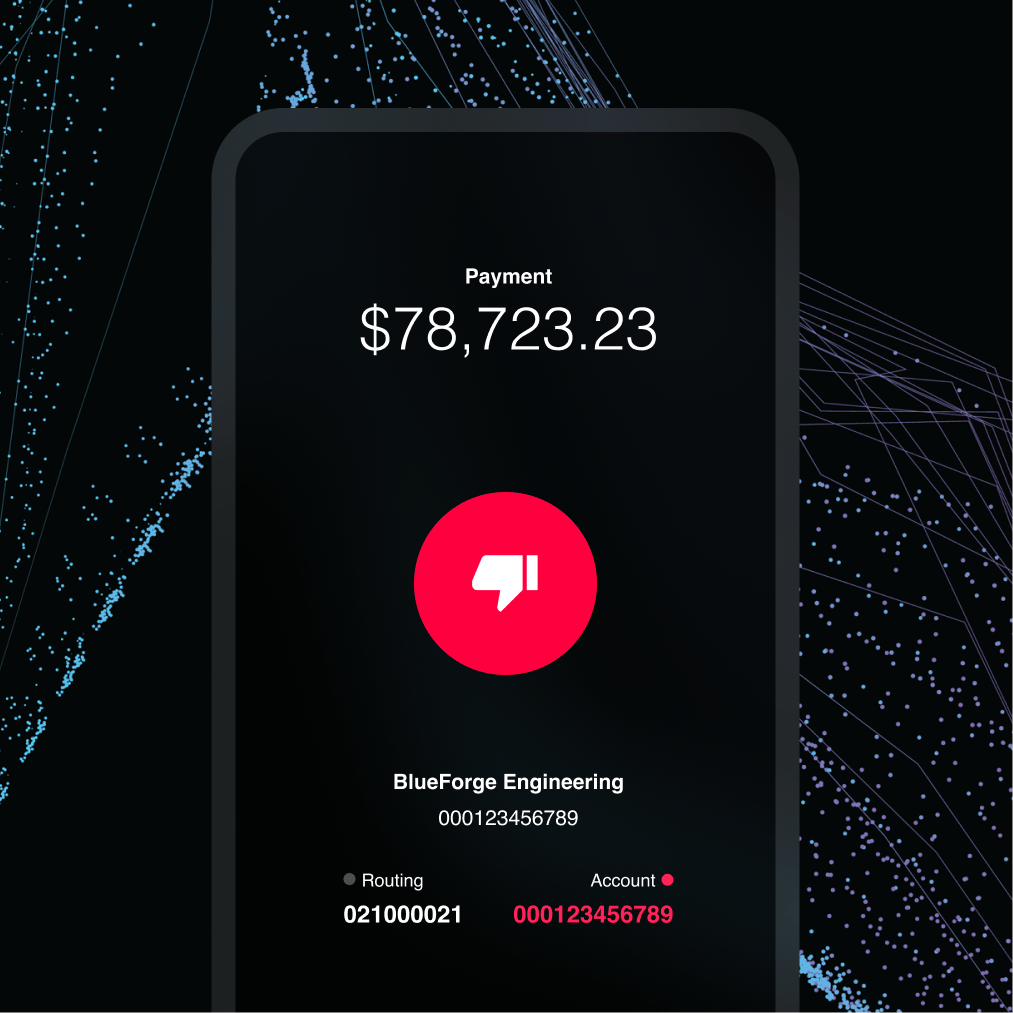

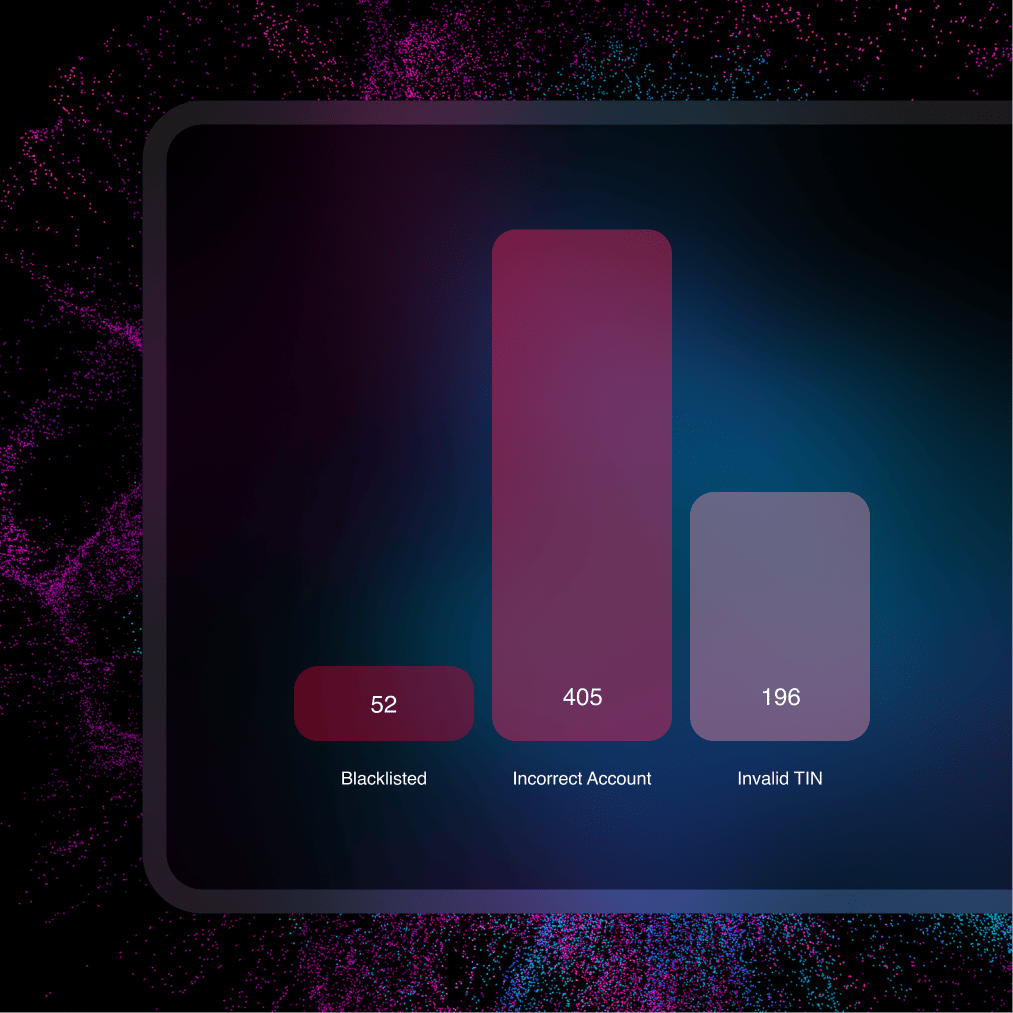

Payment Protection

Prepare, and pay with certainty

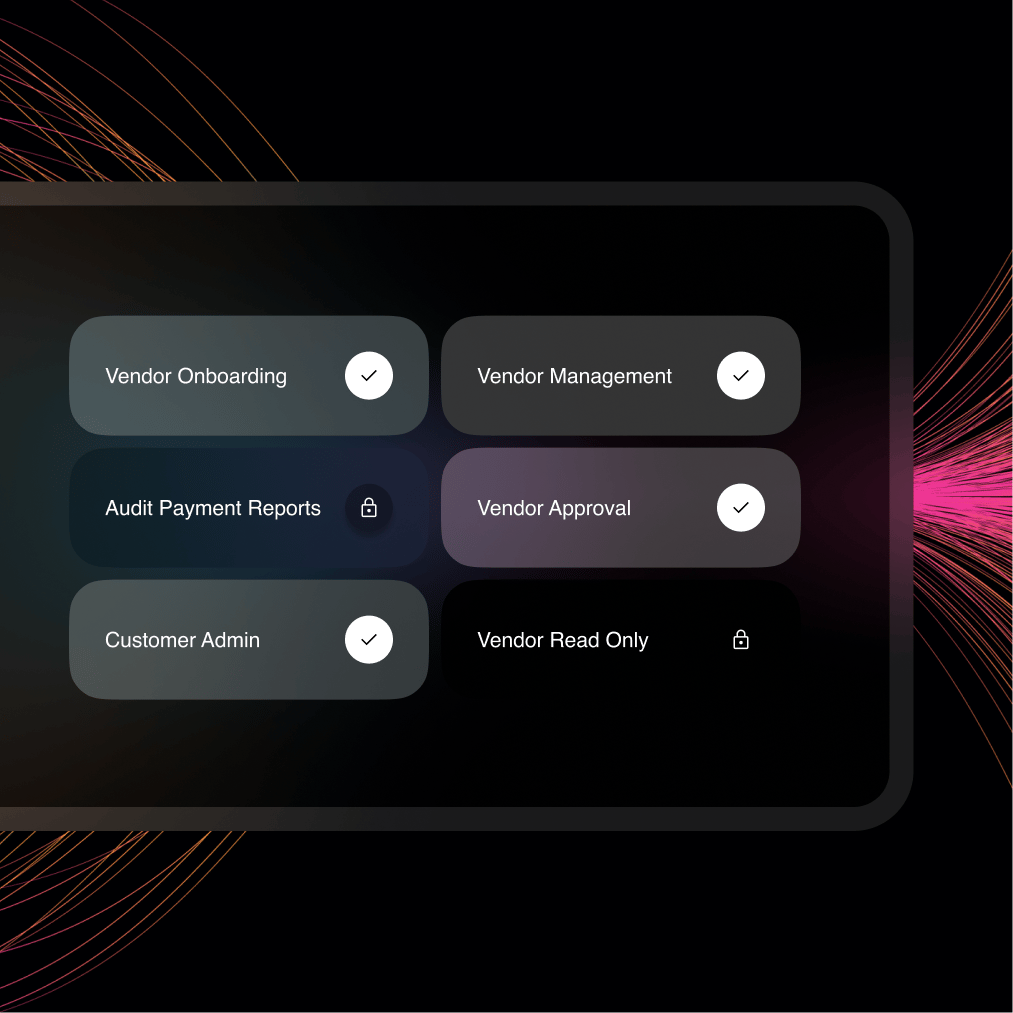

Segregation of Duties

A digital interface to manage visibility and assigned tasks

Audit and Report

Centralise reporting to reduce audit stress

Integrations

Robust integration capabilities with various platforms

By Role

By Threat

AI Deepfake fraud

Safeguard against AI deepfakes

Business Email Compromise

Advanced protection against Business Email Compromise

Insider Threat and Internal Fraud

Detect and deter internal fraud risks

CEO and executive impersonation fraud

Identify and block impersonation attempts

Invoice Fraud

Keep payments safe from fraud